|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Shin hanga printmakers also used two different horizontal formats, one almost squareb (10%) and the other with the width much greater than height (20%). Prints 40 and 41 are examples of these two formats. Ukiyo-e printmakers used only one of these two formats (i.e., width much greater than height). The almost square format was used traditionally for poetic and calligraphic artworkc so its use for pictures of birds by shin hanga printmakers is both novel and surprising. a Percentages are based on a sample of 1459 shin hanga

bird prints by 78 different artists. Their names, signatures and examples of

their prints are included in Appendix 2.

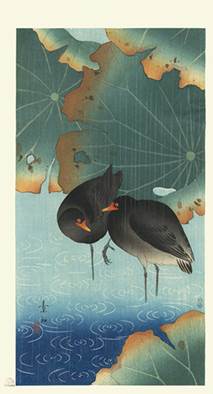

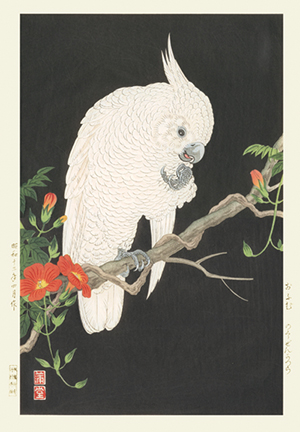

The majority (60%) of shin hanga bird prints had a white border, either on all four sides (e.g., prints 37, 38) or on at least one side (e.g., print 41). In contrast, few (7%) Ukiyo-e bird prints had a border. This difference presumably reflects the fact that many shin hanga bird prints were marketed not only in Japan but also in the west (i.e., Europe and America) where prints were mounted in wooden frames and a picture border facilitated mounting. Shin Hanga printmakers typically included some written information on their prints. Artists signed their name using the kanji alphabet (prints 37, 40, 41) and (or) included their personal seal (prints 37, 38, 39, 41). Publishers added their logo to some prints (10%), either on the print border (print 37) or within the picture area (print 41). The name of the bird subject was also included on the border of a few (10%) prints (print 38). Similar information about the artist, publisher and birds appeared on about the same percentages of Ukiyo-e bird prints. Unlike ukiyo-e printmakers, shin hanga printmakers dated some (4%) bird prints (print 38) but did not include any poetry.

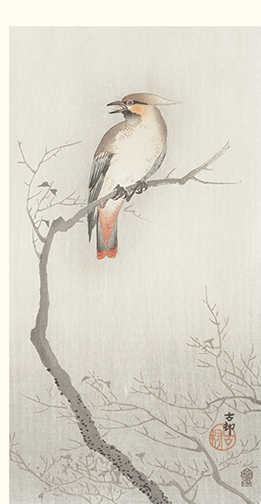

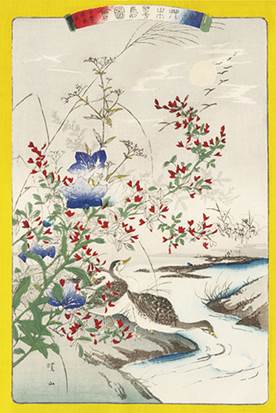

Birds were most often paired with plants, either flowering (53%) or without flowers (33%). Both the plum flowers (Prunus mume) and Eurasian bullfinch in print 42 are associated with the spring season in Japan. The Japanese waxwing in print 43 is a symbol of autumn which is presumably why the artist showed it perched in a leafless tree. Ukiyo-e artists had also paired birds most often with flowering plants (69%) or plants without flowers (22%).

Earth or water also appeared in about a quarter (28%) of shin hanga bird prints. Prints 44 and 45 provide examples of pictures in which they were important components of the design. Ukiyo-e printmakers included earth or water in a similar percentage (27%) of their bird prints.

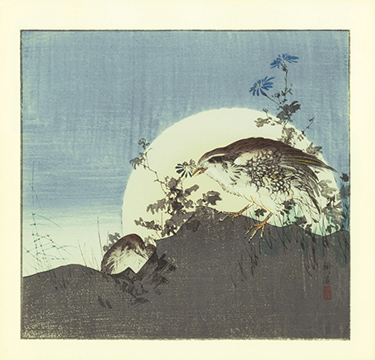

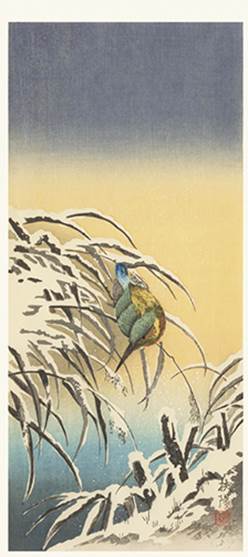

Atmospheric elements were included in more shin hanga bird prints (30%) than ukiyo-e bird prints (17%). The types of atmospheric elements also differed. Rain (print 46) or snow (print 47) was typically featured in shin hanga bird prints while the sun appeared more often in ukiyo-e bird prints. These differences likely reflect the influence of the western art on shin hanga artists, especially western paintings with dramatic, overcast skiesa. a See Conant et al. (1995). The Japanese word mōrōtai, meaning hazy style, was coined to describe the work of western-influenced Japanese artists who emphasized atmospheric elements.

Man-made objects were included in some (5%) shin hanga bird prints, similar to ukiyo-e bird prints (5%). By including a ship’s mast in print 48 the artist portrayed flying cranes in a very novel way, partly hiding them from view. Birds were sometimes paired with humans in ukiyo-e bird prints (3%) but they rarely appeared in shin hanga bird prints (0.1%). In print 49 they are barely visible in the background.

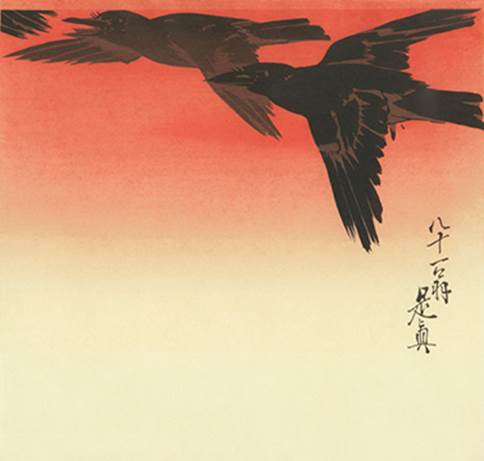

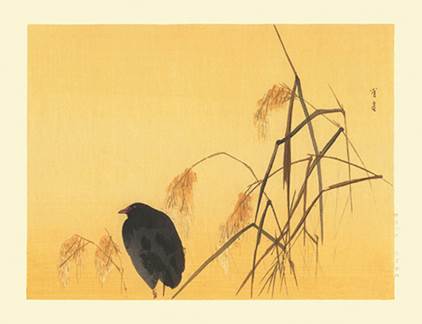

No other objects accompanied birds in some (4%) shin hanga bird prints, typically when birds were flying as in print 50. In contrast, birds were rarely unaccompanied (0.5%) in ukiyo-e bird prints.

Bird Species Chosen for Depiction Shin hanga printmakers chose a wider rangea of naturally occurring bird species for depiction than ukiyo-e printmakers but the most popular bird families were largely the sameb. The five most popular families were (1) fowl and pheasants (38%c), (2) egrets and herons (33%), (3) sparrows (32%), (4) ducks and geese (29%) and (5) cranes (24%). The species chosen most often from these five families are described below. a 152 species from 51 bird families were chosen by shin

hanga printmakers in the 1459 prints examined compared to 87 species from 41

bird families chosen by ukiyo-e printmakers.

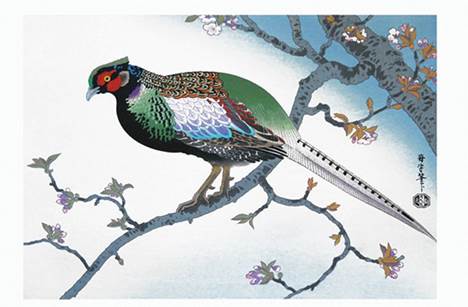

(1) Fowl and Pheasants (Phasianidae)

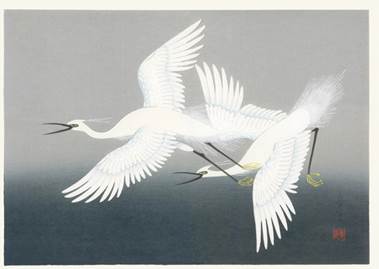

(2) Egrets and Herons (Ardeidae) The little egret (print 54) and black-crowned night-heron (print 55) are the two members of this bird family usually depicted by shin hanga artists. Both are common in Japan, found in a variety of shallow-water habitats, and are symbols of the summer season. The little egret is also a symbol of purity and delicacy because of its pure white feathers and relatively small size.

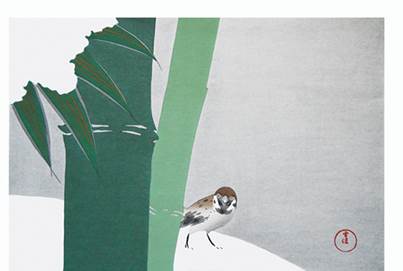

(3) Sparrows (Passeridae) The Eurasian tree sparrow (print 56) is one of the commonest wild birds in Japan. It was often accompanied by snow in shin hanga bird prints due to its symbolic association with winter.

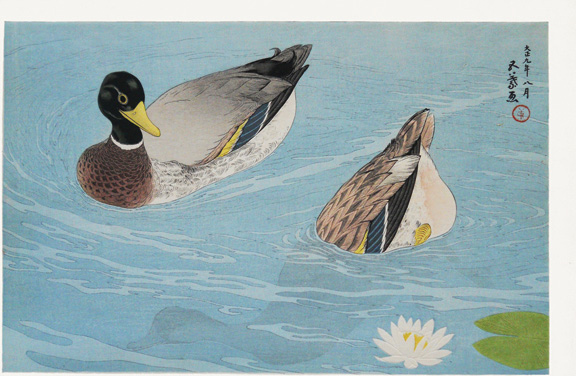

(4) Ducks and Geese (Anatidae) Similar to ukiyo-e bird prints, the mallard duck (print 57) and white-fronted goose (print 58) were popular choices for shin hanga bird prints. Also similar to ukiyo-e bird prints, descending birds were often shown with a full moon in the background or with snow on the ground.

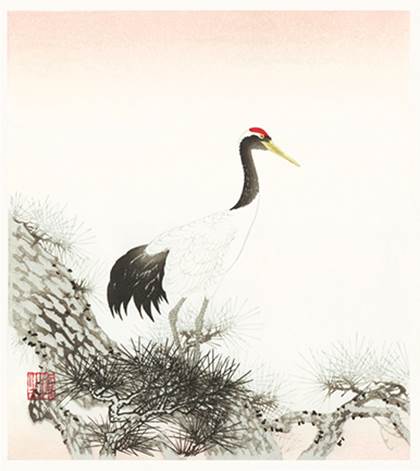

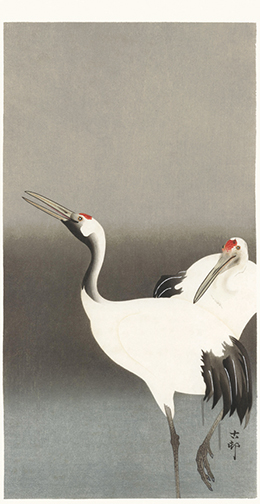

(5) Cranes (Gruidae) Shin hanga artists only depicted one of the two species of cranes chosen by ukiyo-e artists; namely, the red-crowned crane (print 59). It was often paired with the pine tree because both are symbols of longevity in Japan.

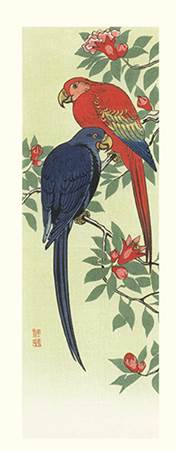

Many (43%) of the bird species chosen for depiction by shin hanga printmakers did not appear in ukiyo-e bird prints. Some of these birds would have been unknown to ukiyo-e printmakers. The two species of South American macaws depicted in print 60 are good examples. They were likely first brought to Japan when trade began with Americans in the late 1800s. Of the other speciesa chosen exclusively by shin hanga printmakers only a few (8%) had any symbolic association. Since most (92%) birds chosen for depiction by ukiyo-e printmakers had a symbolic association these other species may have been of less interest. a These other species include white-cheeked starling (print 41), white-winged widowbird (print 68), Ryūkyū robin (print 76), tufted duck (print 78) and olive-backed pipit (print 84).

Perhaps the most obvious difference

between shin hanga and ukiyo-e bird prints is the accuracy with which birds

were drawn. Shin hanga artists with western art training typically drew birds

more accurately than ukiyo-e artists. The later had been influenced by the

Chinese philosophy of art in which accuracy of depiction was sacrificed to

reveal the bird’s inner spirit. In contrast, the objective of traditional

western art was to show the external features of the bird subject as

accurately as possible without concern for any possible inner spirita. a Most westerners do not believe in the spiritual equality of birds and humans because the dominant western religion of Christianity has taught them that animals are inferior to humans in both body and spirit. In contrast, far-eastern religions such as Buddhism and Shintō teach that all animals are endowed with a spirit, not just humans.

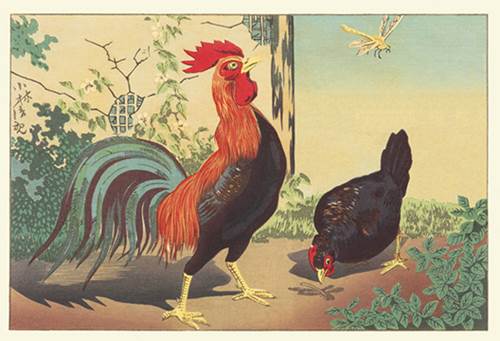

Birds were drawn only semi-accurately in the other 30% of shin hanga bird prints. Some artists who were influenced by western watercolor painting used graded color to the extreme and created blotchy looking subjects with indistinct shapes. Print 63 is an example. Other artists did not use graded coloring at all so their birds look two-dimensional instead of three-dimensional. Print 64 is an examplea. Note that both the domestic fowl and dragonfly in print 64 cast shadows which is another influence of western painting style on shin hanga bird art. a See print 37 for a more accurately drawn common moorhen and print 39 for a three-dimensional domestic fowl.

.

Shin hanga printmakers used the

woodblock printing technique to make their bird prints, similar to ukiyo-e

printmakers. The inks used for printing by ukiyo-e printmakers were made by

mixing water with naturally-occurring pigments which had been extracted from

various plants, animals, rocks and earth. a The lower cost of synthetic pigments is presumably responsible for this difference.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Notable Artists or Back to Guides

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||